Alain Arias-Misson, From the Cutting-Floor of the Public Poem

Softcover, 80 pp., offset 4/1, 165 x 245 mm

Edition of 2000

ISBN 978-94-9069-315-2

Published by MER. Paper Kunsthalle

$32.00 ·

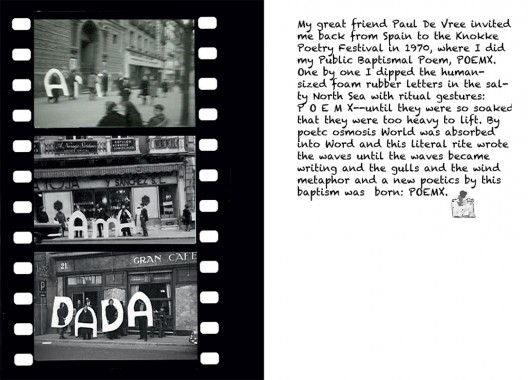

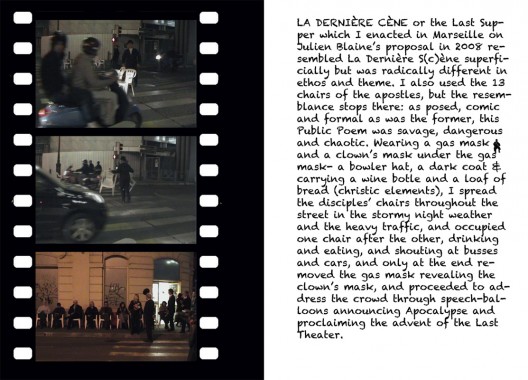

Alain Arias-Misson created the “Public Poem” 45 years ago in Brussels and Madrid when he decided “to write on the street like a page.” From the Cutting-Floor of the Public Poem gives a graphic account of this always disruptive urban poet — from the Place St.-Germain in Paris to the Sixtine Chapel in the Vatican and Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Alain Arias-Misson, Art, Distribution, MER. Paper Kunsthalle, New York, Performance, Poetry, Roger D'Hondt

Medium 1, Poetry

Softcover, 64 pp., offset 4/4, 165 x 240 mm

Edition of 500

Published by Nieves

$14.00 · out of stock

Today there was a guy leaning the wrong way in the tube. It was not immediately noticeable. There was no one else sitting nearby. No other passengers to compare him to. But then I did notice that every time the carriage came to a stop, he leaned away from the direction we were moving. Very slightly. Think about it. You’re supposed to lean forward. In the direction you were moving toward. Toward the point which the weight of your body was expecting to reach. Now this guy, he leans the other way. Just slightly. As a friend of mine would put it, he has a great sense of irony. Definitely. That’s important in life. They say that Rothko, he killed himself because he met the people who bought his art. No sense of irony. Me neither I don’t have any sense of irony. I like to take things at face value. Your wife she once told me that what led to the demise of the Black Panthers, aside from the absence of trust, and a murderous governmental incarceration campaign, it was their complete lack of a sense of humor. It was only much later that I realized she meant a murderous governmental incarceration campaign is actually a lot worse than not having a sense of humor. But these ironies are lost on me. Your sister and your wife they both say so. When I tell them things I find funny, they rarely laugh. I’m not even going to mention this guy in the tube to them. I recently told them about my bathroom sink in this hotel room. Real bad design. Flat. Which meant the liquid always accumulated in the corners. Instead of flowing down the drain. You had to use your fingertips to fish out the shaved hair stubble from the corners of the sink. Or it would just lie there. Waiting. You know what’s even funnier: you had to try and propel what you spat out when you brushed your teeth towards the center of the sink. Or you’d have mounds of mucus and toothpaste. Just drying in small heaps, here and there. Hilarious. And speaking of heaps of mucus. Another thing I’ll keep to myself – this was the funniest thing in years: I saw an old couple smooching in the street the other day. How often do you see that. Teenagers, yes. Or oldies arm in arm. But here you had oldies with their tongues down each other’s throats. Right there in the pedestrian zone. Eighty years old maybe more. Couldn’t believe it. I just stood there laughing. These oldies have no sense of humor either. They pretended not to hear me. But I could tell they heard me perfectly well. So now the carriage starts moving again, and I stand up, knowing I’ll exit at the next station. You see there are things I’m less sure about. Are they funny or just poetic. Lately my eyeballs scrunch as I close my eyes. A crunching sound. Brief, almost imperceptible. The sound is a bit like high-tech mechanics when they start aging. Wearing out. A whispering scrunching sound. Funny, or lyrical? Now as I exit the carriage, I notice there’s vapor in the air as I breathe, despite the high temperatures. It’s been like this all week. Again, very odd and almost funny. In a tiny, barely noticeable kind of way. Like the guy leaning the wrong way back there. As the doors slam shut, I turn around to look for him. I want to see which direction he’s leaning in as the train departs. Before I can assess his movements, he smiles and waves. I wave, but I fail to smile back. It’s just not funny anymore.

Art, Bastien Aubry, Culture, Distribution, Hassan Khan, Manuel Krebs, Nieves, Poetry, Samuel Nyholm, Shirana Shahbazi, Tirdad Zolghadr

Marc Hundley, Weaverbird & Other Words

Hardcover, 68 pp., offset 4/4, 183 x 251 mm

Edition of 500

ISBN 978-0-9806516-2-1

Published by Rainoff Books

$40.00 ·

First monograph by Canadian-born, New York-based artist Marc Hundley, traces a curated-selection of his divergent work from the beginning of the century until present.

Art, Distribution, Marc Hundley, Photography, Poetry, Rainoff Books, Typography

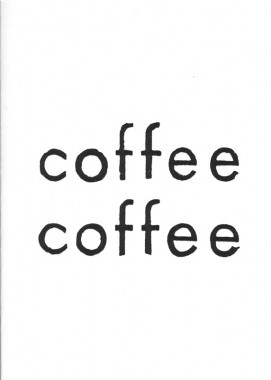

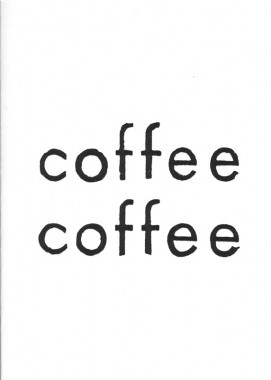

Aram Saroyan, Coffee Coffee

Softcover, 88 pp., offset 1/1, 5 x 7 inches

Edition of 1000

ISBN 978-0-9788697-5-5

Published by Primary Information

$10.00 ·

Infamous artist book by one of the 1960s most controversial poets.

Coffee Coffee was originally published as a mimeographed edition by Vito Acconci and Bernadette Mayer on their 0 To 9 press in 1967. True to Saroyan’s minimalist approach of the time,

Coffee Coffee’s pages contain one word (sometimes 2 and once or twice, 3), each pulling you to the next (revolving door-like). Selections from

Coffee Coffee appear in the recent anthology

Complete Minimal Poems (Ugly Duckling Presse) edited by Primary Information co-founder James Hoff; however, this is the first time that this work has appeared in its complete and initial form since 1967.

“In the late Sixties, when I called myself a poet, Aram was the poet I envied. Because you couldn’t be sure if he was fooling or if he had really gotten to all there is to get. Because while the rest of us tried to be verbs, like everybody told us to do, he had the nerve to stop at nouns. Because he took a deep breath and willed himself into the self-confidence of naming. Because it wasn’t ‘nouns,’ it was ‘noun,’ only one noun, because he boiled it all down to one. Because then he let himself go, he let himself stutter, he let the one go and let the one double and go out of focus: while the rest of us ran for our lives all over the place and over the page, his noun shimmered and breathed and trembled and moved-shh! softly, softly-from within.”

—Vito Acconci

Aram Saroyan, Art, Bernadette Mayer, DAP, James Hoff, Performance, Poetry, Primary Information, Vito Acconci